I used to read the news every morning and thought this was a good thing. I’m sure that at some point, I thought more people should do it because it’s important to be an ‘informed citizen’. It wasn’t just a thing I did, it was a duty.

I’m sure I got this habit from my dad. He’s woken up by the news with his radio and continues listening to it on his way to work. He’s an extremely informed person and can probably tell you anything about politics on demand.

However, as I’ve grown up, I’ve strayed from my dad in this respect. I no longer read the news every morning and don’t think it’s necessary for anything.

In fact, I want to read the news less.

This is what this post is about. Reading less news and reducing the needless amount of information we consume every day for greater clarity, focus and more happiness.

Most of the links supporting my argument will be at the end (so you don’t have an endless number of tabs open at the end).

What is the Low Information Diet?

Consuming less information.

Mainly the news but it can also include blogs, internet forums and, email and so on.

There are a number of reasons for this and I think they support the aim to consume less information on a daily basis so we can pursue other interests and be more involved in our own lives through active engagement rather than passive participation.

Removing the passive aspect of news consumption means we’ll make a more deliberate effort with the information we consume and become more likely to consume higher quality information.

Why bother?

I want to highlight a few important reasons why we should consume less news and information. I will also address a few problems people might have.

A lot of this is inspired by the essay Avoid News: Towards a Healthy News Diet by Rolf Dobelli. I don’t agree with everything he says but that’s not terribly important.

News is harmful

It is sometimes beyond useless.

The overwhelming majority of news is negative. Studies have shown the average ratio is 17:1 or 95% negative news!

You may come to the conclusion that it’s just the way the world is.

I was part of a lecture given by two BBC News journalists where they taught us how to create compelling headlines and write stories. There was a Q&A session at the end and I asked one of the women what she thought about the lack of positive news in the media.

“Positive news doesn’t really go anywhere.”

You can create stories from a murder investigation but stories about literacy rates increasing or cured diseases tend to stop after one news reel. It may be true that positive stories and tend to lack new developments the same way a negative one would but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. Since news stations (even government-funded ones like the BBC) require views, they’re far more likely to include prolonged negative stories rather than standalone positives.

This attitude is compounded at times. Myself included. The attitude of ‘positive news isn’t real news’ pervades our thinking far too often. If we hear about an explosion that’s killed 30 people but see the news reporting about plastic bag use decreasing (which has important consequences for our environment) we might think to ourselves ‘This isn’t news. Why are they wasting my time?’

It’s unfortunate because it hides the good in the world using the excuse of ‘I want truth’ which is really a veil covering needless cynicism.

Assuming the world is bad and wanting the news to confirm that belief that is not truth-seeking. It’s ego-stroking.

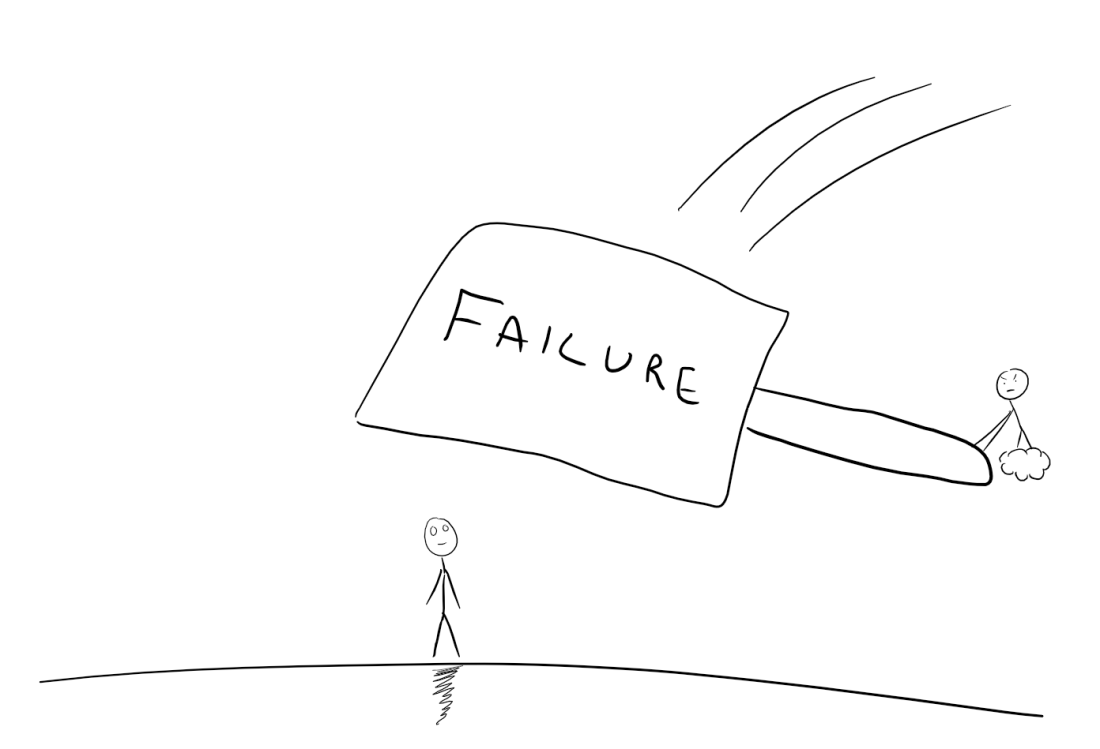

Being bombarded with negative news is very good at causing anxiety.

We get facts about some disaster and feel bad about it. It doesn’t affect us directly so we don’t do anything to help apart from say ‘that’s really sad’. Then we feel bad about something we can’t change.

For a lot of people, the news doesn’t inspire the amount of action that’s proportionate to the news we watch every day. So a lot of the time, we’re entertaining feelings of depressed helplessness.

It’s rarely substantial

Most of the news we read or watch isn’t substantial. They’re bound to be very short articles without much investigation. That’s the nature of first-then-fact news. These pieces are bound to just make us feel bad about an event without discussions (not assertions) about why the event happened or what progress is being made on the problem.

There are many brilliant articles and journalistic pieces out there. They take time and effort to both create and digest. The feelings they create whether positive or negative are a result of active engagement rather than a simple fact devoid of proper discussion.

You can test this yourself. Think about the number of articles and news pieces you’ve read today and count the number of things that have made a substantial effect on your day. The number is probably low. Unfortunately, if you haven’t already spent time curating your sources of information, then the ratio of useless to engaging will be skewed in the wrong direction.

Not everything you read or watch needs to be life-changing. That’s a high ask.

The aim here is to focus our attention to sources of information or activities that improve the quality of our lives and the time we spend taking part in the activity. A trip in the 24 hour news cycle is unlikely to do that.

Dobelli’s point here is important. He says it’s difficult to recognize what’s relevant but much easier to recognise what’s new. The news always offers us new things but can’t always be relevant to our own lives on a consistently enough to justify following it every day.

If something is relevant, the chances are we’ll hear about it from someone else who follows the news or from more specialised sources.

If we miss out, the world will keep on spinning and your day will keep on moving forward.

No, you won’t be boring

A fear I’ve heard expressed is that we’ll become boring if we don’t stay up to date with the news because we’ll have nothing to talk about.

It’s true that some small talk focuses on current events but I don’t think this is particularly important. There are two reasons for this:

- News isn’t much to bond over.

It’s much more useful to take interest in the person you’re talking to rather than a news event that has a high chance of just creating pity.

- Consuming higher quality information leads to higher quality conversation.

This does not mean academic information. If we focus on things we find really engaging (that can be reading a comic, book or watching a film etc.), we’ll be happier talking about them to other people and others will be happier to learn about them.

I’m confident that the best conversations you’ve had did not revolve around the most recent news event at the time.

If current events do come up, it means you’ll learn something new.

Don’t worry if it’s daunting to always say ‘I didn’t hear about that’ (not that there’s anything wrong with it). This information diet does not necessarily require no news at all but a deliberate reduction.

Too much information ruins our attention

While I think the other points are important, I find this is particularly potent because it expands beyond the problems of the news.

There’s only so much time and energy we have every day to focus our attention on certain things. Bombarding ourselves with more information day every forces us to make many decisions about small things.

Nicholas Carr wrote an article expanding on this problem. A study was completed in 2007 analysing what happens to brain activity when novices to the internet begin browsing the internet for prolonged times. Their brain activity increased significantly but that didn’t automatically mean better brain activity. They were more likely to skim articles, and become more shallow thinkers.

This doesn’t mean skimming is bad. It’s a vital skill but clearly cannot become the only way we consume information. If not for the fact that slower and deeper reading leads to better comprehension, keep in mind that being engaged with activities is a key ingredient to being happy.

What can you do instead?

One complaint about the low information diet is that you might not have anything else to do. Another is that being fully engaged with activities is often tiring. Here are a few suggestions:

- Read a good book/article

- Talk to people

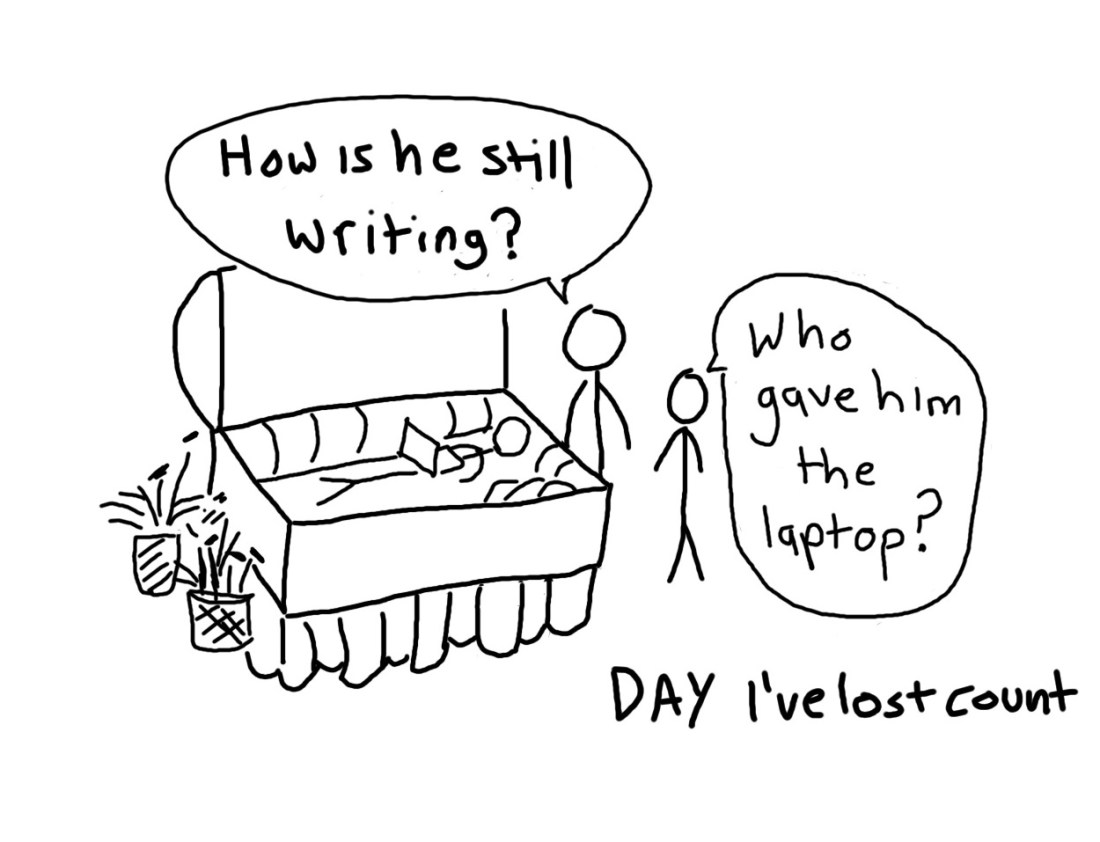

- Write a journal about your day

- Look around and take in your surroundings (I’m serious)

- Listen to music

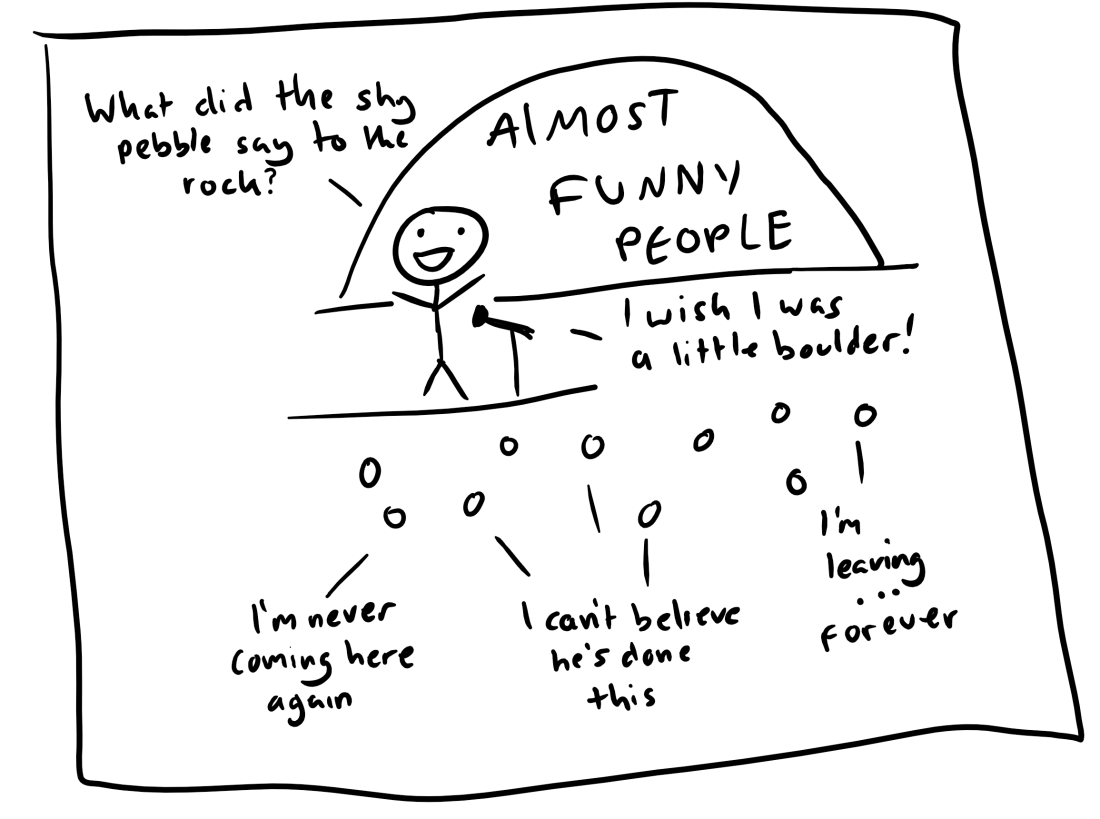

- Watch a movie or enjoyable videos (stand-up comedy is an example)

There are many things you can do which don’t require a lot of mental energy which are still enjoyable and remove us from anxiety-inducing news.

The Low Information Challenge

You might not be convinced by this.

I wasn’t at first and feared that I would lose my privilege as an informed citizen. None of that happened. I’ve strayed from this and wish to go back. Here’s a challenge that we can do:

- No news for one day. Then a week. If you can keep on going, even better.

It will require a deliberate effort since checking the news tends to be an ingrained habit nowadays. That’s why we’re starting off small rather than diving into never reading the news again.

If that sounds too difficult or simply absurd try the softer version.

- Restrict news consumption to 10 minutes at the end of the day

Rather than welcoming endless streams of information, we limit it on purpose.

I recommend trying going cold turkey first though. There are benefits to just not reading the news at all.

In a month, I’ll report back about how the low information challenge went. I hope you join in too!

‘til next time.

Sign up to my fortnightly newsletter for free updates on my best posts.

Share this post on Facebook or Twitter!

Further Reading:

Avoid News: Towards a Healthy News Diet by Rolf Dobelli [PDF]

A short objection to Dobelli’s article (highlights some of the disagreements I have with Dobelli)

The Low Information Diet (Mr Money Moustache)

News is 17:1 negative – Studies like this tend to be he-said-she-said where they’re repeated ad nauseam without a source. I found one in Democracy Under Attack: How the Media Distort Policy and Politics by Malcolm Dean p.415 (he actually has it at 18:1)

Why We Love Bad News More Than Good News

Why Bad News Dominates Headlines (very good discussion about our tendency to say we want good news but read bad news)

The Power of Ignoring Mainstream News

Some Great Articles:

The Blind Man Who Taught Himself to See

Lionel Messi is Impossible

How David Hume Helped Me through my Midlife Crisis

This blog I found is full of them…

If you have any recommendations, feel free to mention them below!

If you liked this post, share it with others!